Information and information skills have a tendency to become fragmented in the organization as the organization specializes in its functions. Traditionally, librarians would look after the organization’s collection of printed information, record managers would maintain internal files and documents, while information technologists would design and build computer-based systems to process operational data. The information user, the raison d’être for all this flurry of information activity, is often only episodically or peripherally involved, and a gap results between their real information needs for decision making and the information captured and delivered through the organization’s information systems and services.

The intelligent organization breaks away from this functional fragmentation and forges new partnerships that bring together the organization’s capabilities to create and use knowledge, organize knowledge, and build infrastructures that enable the effective management of knowledge. At the heart of the intelligent organization are three groups of experts who need to work together as teams of knowledge partners: the domain experts; the information experts; and the information technology experts (Table 2).

The domain experts are the individuals in the organization who are personally engaged in the act of creating and using knowledge: the operators, professionals, technologists, managers, and many others. The domain experts possess and apply the tacit knowledge, rule-based knowledge and background knowledge that we have discussed earlier in their day-to-day work, interpreting situations, solving problems, and making decisions. The knowledge and expertise they have is specialized and focused on the organization’s domain of activity.

Through their coordinated effort the organization as a whole performs its role and attains its goals. Through their knowledge creation and use, the organization learns, makes discoveries, creates innovations, and undergoes adaptation. The information experts are the individuals in the organization who have the skills, training and know-how to organize knowledge into systems and structures that facilitate the productive use of information and knowledge resources. They include librarians, records managers, archivists, and other information specialists.

In organizing knowledge, their tasks encompass the representation of the various kinds of organizational information; developing methods and systems of structuring and accessing information; information distribution and delivery; amplifying the usefulness and value of information; information storage and retrieval; and so on.

Their general focus is to enhance the accessibility and quality of information so that the organization will have an enlightened view of itself and its environment. The information experts design and develop information products and services that promote learning and awareness; they preserve the organization’s memory to provide the continuity and context for action and interpretation.

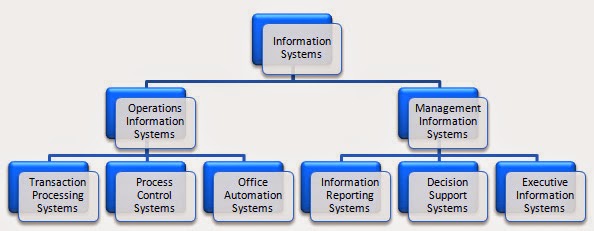

The information technology experts are the individuals in the organization who have the specialized expertise to fashion the information infrastructure of the organization. The information technology experts include the system analysts, system designers, software engineers, programmers, data administrators, network managers, and other specialists who develop computer-based information systems and networks. Their general focus is to establish and maintain information infrastructures that models the flow and transaction of information, and accelerates the processing of data and communication of messages.

The information technology experts build applications, databases, networks that allow the organization to do its work with accuracy, reliability, and speed. In the intelligent organization, the knowledge of the three groups of domain experts, information experts, and IT experts congeal into a superstructure for organizational learning and growth.

In order to work together in teams of domain experts, information experts, and information technology experts, each of them will need to re-orientate its traditional mindset respectively.

Users as domain experts will need to separate the management of information from the management of information technology. Information technology in most cases has been heavily managed, whereas the management of information processes—identifying needs, acquiring information, organizing and storing information, developing information products and services, distributing information, and using information—has been largely neglected. Users need to understand that the goals and principles of information management are quite different from the objectives and methods of information technology management.

Users could participate fully in these information processes, not just as end-consumers of information products or services, but as active agents in every activity of the information management cycle, especially in clarifying information needs, collecting information, sharing information, and transforming raw data into useable information.

Users should share the responsibility of identifying and communicating their information needs, and not abdicate this work completely to the information or information technology experts. The most valuable information sources in the organization are the people themselves, and they should participate actively in an organization wide information collection and information sharing network.

IT experts are the most prominent group in today’s technology-dominated environment. The management of information technology has remained in the media’s spotlight for many years now, with no signs of diminishing interest. Academics, businesses, consultants, and government all continue to extol the strategic application of information technology. IT experts have indeed become proficient at fashioning computer-based information systems that dramatically increase operational efficiency and task productivity.

At the same time, the very same systems that are so remarkable for their speed and throughput are equally well known for their inability to satisfy the information needs of the decision makers. By representing and manipulating information at the data-element level, many systems do not provide more holistic information about processes, subject areas, or even documentation matters.

Thus, an information system that processes vast numbers of transactions per minute may be unable to answer key questions like how long does the company take to develop new products, what is the firm’s current market share, and what is the turnaround time for a customer order. Computer-based information systems concentrate on formal, structured, internal data, leaving out the informal, unstructured, external information that most decision makers require.

Their operating criterion is efficiency over flexibility, and they are designed to optimize resource utilization rather than to simplify knowledge discovery or problem solving. IT experts need to move the user to the center of their focus—develop a behavior-based, process-oriented understanding of the information user in terms of their needs and information use dispositions. People in organizations are not content with structured transactional data; they also want information technology to simplify the use of the informal, unstructured information that forms the bulk of the organization’s information resources. http://www.InfosDemocracy.com